So we have a new sous chef at work. He saw a video on You Tube of

Chris Consentino making Porchetta di Testa, and wanted to try it at the restaurant. What is porchetta di testa? Well it is basically a pig's head that is boned out, marinated, then rolled up, tied, and wrapped, then slow braised for 14 hours. How psyched was I when my sous chef ordered two heads and offered to let me make one?!

DAY 1 - Deboning the head, face to face

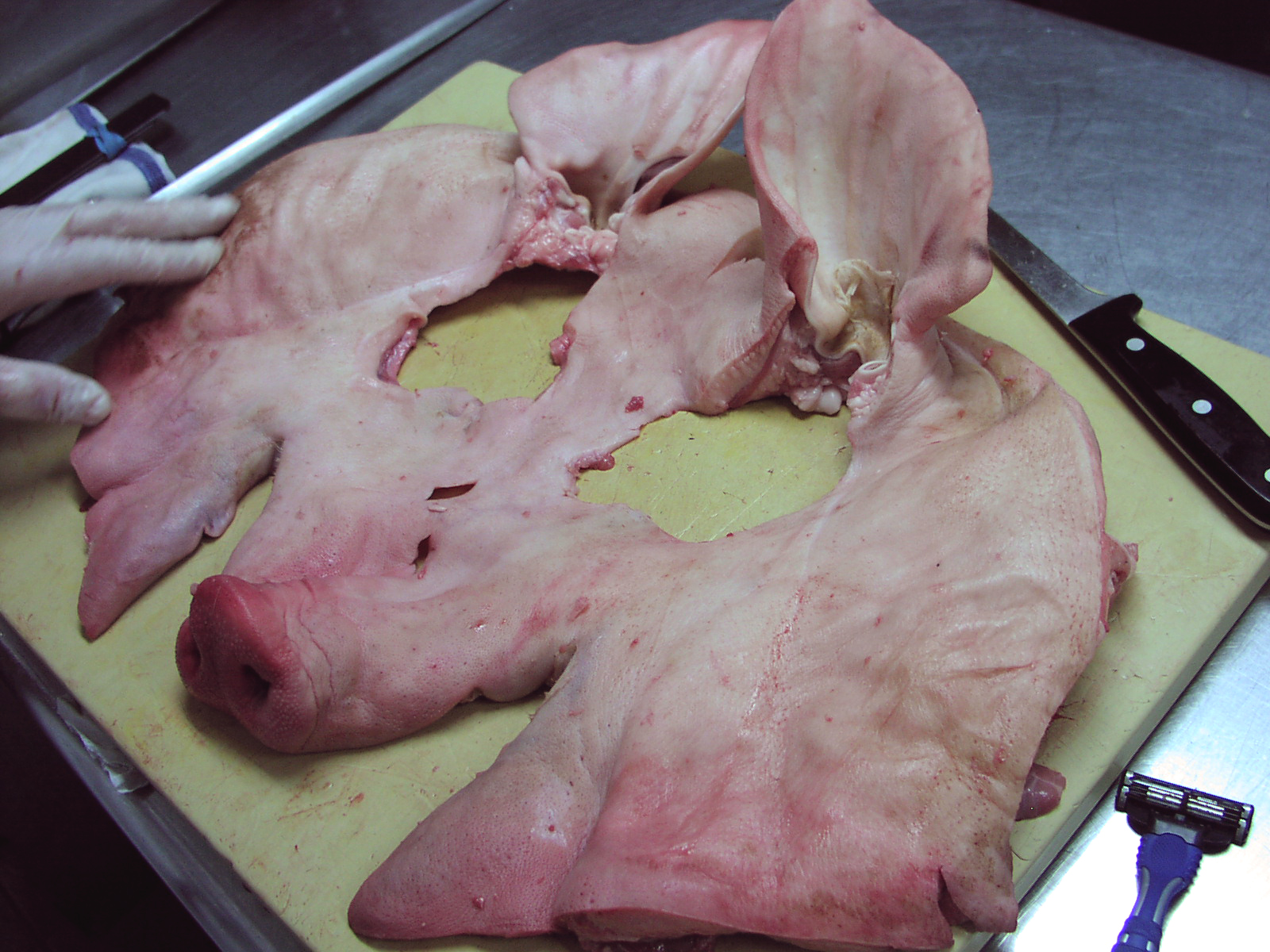

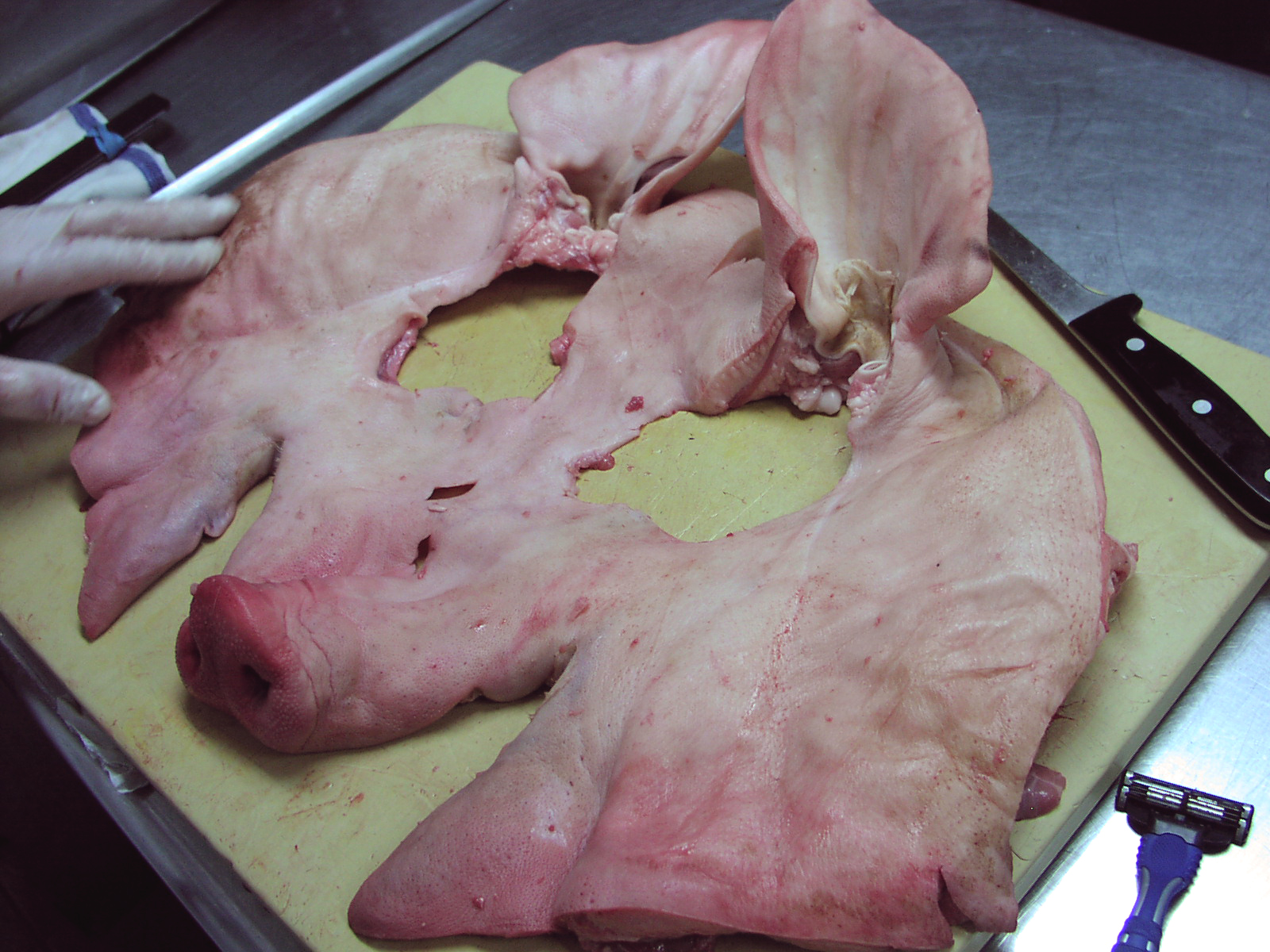

I arrived at work early for Day 1 of Project Porchetta. My sous chef demonstrated on one pig's head while I looked on and snapped some photos. As he turned the head upside down to get at its chin, some blood spilled out of the snout. There was no avoiding the reality of the animal. Here I was, staring at its bloody nose, and tongue hanging out the side of its mouth. The heads that we received from our meat purveyor had some of the flesh around the eyes already cut away, but the eyes were still there. Some say they can't eat an animal that is staring at them (like whole fish, head on), but really, there was no life left in the eyes of this pig. It wasn't staring at anything. I was transfixed, and my sous chef admitted to being a little surprised at how un-squeamish I was about the process. He cut his way from the chin to the snout on the underside of the head, exposing the jowls and teeth, then turned the head around and released the skin and flesh from the crown down the top of the snout. In about 15-20 minutes, the skull was separated from the face, and the tongue from the skull. Until then, I had no idea what a pig's skull looked like. What came off of it, aside from the fleshy underside of course, looked just like a halloween pig mask. Dares to wear it ensued among the prep crew.

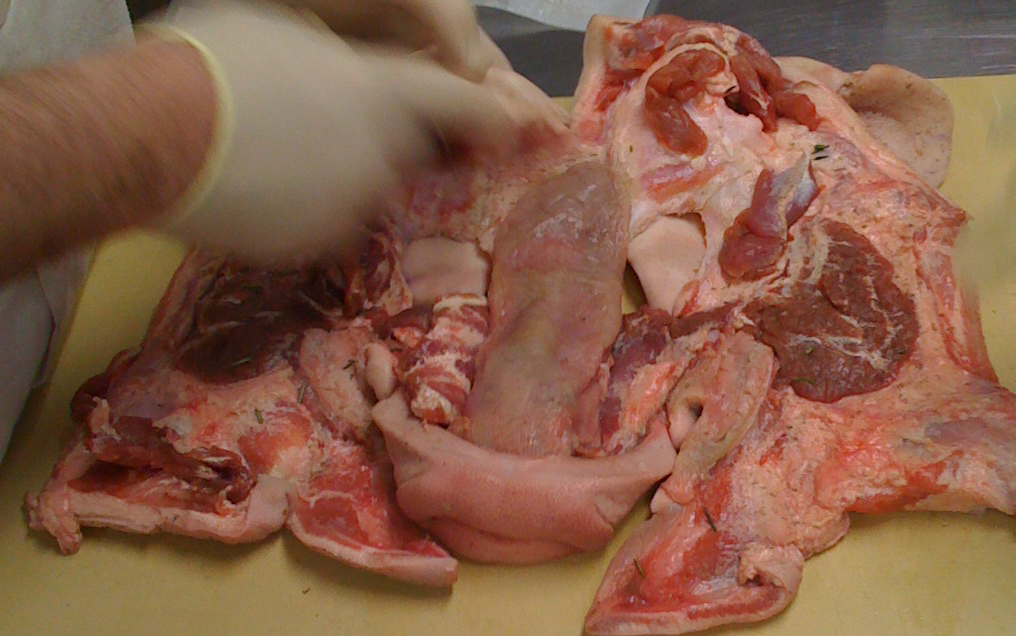

Then it was my turn. The first thing I noticed was the weight of the pig's head. It was easily 20 pounds (by feel, it seemed heavier than my cat, but lighter than my dog). Using a disposable gillette razor, I shaved remnants of bristle from its brow, cheek, and chin and cleaned debris and wax out of the ears. A brief once-over with a torch removed any stubble left behind by the razor. Then, as my sous chef had done, I turned the head over (another bloody nose) and started cutting at the chin. Pulling at the flesh, I used the tip of my knife to slowly separate it from the jawbone. My goal was to leave the skull as clean as possible, leaving most of the meat attached to the skin. I was thankful to have the other pig's skull next to me so I could see what I was looking for underneath everything. My sous chef left me to my work, remarking to the prep cooks that I was "mucha macho," as our house butcher looked on approvingly. I guess they weren't used to seeing a woman so enthusiastic about butchering hog. Anyway, there were several different muscles and a lot of connective tissue under the jaw, making it extra tricky to figure out where to cut. Cutting away the top of the head was a little easier. There wasn't a lot of flesh there except for the cheeks, so I had to take it slow not to cut through the skin. The last step of taking the mask off the snout was definitely a two-person job. I tried to do it myself, but the pig mask was cumbersome - just flapping around - and there was no way to rest the skull steadily. One person needed to pull on the skull while the other pulled on the mask and cut away at the cartilage of the snout. After separating the mask from the skull, I pulled open the jawbone to get at the tongue, then pulled the tongue down through the jaw and separated it from the skull a its base.

We generously seasoned both masks inside and out, and the tongues with salt, pepper, and herbs and wrapped them tightly in plastic. Then they were placed in the refrigerator to cure/marinate. We marinated the first one for only one day, mine for two days.

DAY 3 - Tie and Braise

After two days of curing, I unwrapped my pig's head and removed all the herbs. Unlike what was shown in Chris Consentino's video, we had left the ears on on the pig face. So before rolling the mask, we tucked the tips of its ears into the eye holes. We put the tongue inside the snout, and rolled the whole thing up, tucking in the ends.

We tied up the package, wrapped it in several layers of plastic wrap, then in aluminum foil. Finally we tied up the wrapped package and braised it overnight for 14 hours in a large pot of water on an induction cooktop set at 180-190 degrees. We learned, from having braised the first pig head the night before, that even if I filled the pot to the brim at closing, by the time my sous chef arrived the next morning, so much of the water would have evaporated that the porchetta would be only half covered. So this time we had to make sure that the night crew that came in to clean would periodically check in and refill the pot if needed.

DAY 4 - Cool and Set

Although I was happy about having a day off from work, I was disappointed that I wouldn't be there to see this step through with the pig's head I had started. However I had seen the the porchetta that my sous chef braised the day before hanging in the walk-in. After braising, he removed the porchetta from the liquid, cooled it down, still wrapped to let the gelatin set back up. In my absence, he would also take care of this step for the second one.

DAY 6 - Slice and Serve

Ah, the day of reckoning. It has been almost a week since I started out face to face with the pig's head (more, if you count the time it took to defrost it). On day three, while we were rolling the porchetta that I had deboned, my sous chef remarked "this is your baby too." He had, inadvertently or not, stumbled onto a very fitting metaphor. In a way, it was my baby (wait, does that make him my Lamaze partner?) Here was this humble pig's head, a part of the animal most Americans don't ever want to associate with ham and cheese sandwiches or juicy pork chops. I lovingly and with much care, deboned it, seasoned it, and rolled it. I made sure that there was someone to babysit the entire 14 hours it braised, then I entrusted someone else to take it out, cool it and hang it. In many ways the past 6 days have been like a gestation period. I had no idea what to expect. Did I wrap it tightly enough? Would the fat and gelatin set? Would there be to many air pockets? I was giddy with anticipation, when today, we finally unwrapped that baby, sliced it and tasted it. Was it good? Hmm-hmm, come to mama...